Welcome, reader, to the first in a long, ambiguous timeline of lost historical events curated and retold by yours truly. It’s important that we understand where we come from so that we will have direction where we’re going. Here, we will pick up the pieces of who we were, who we are, and who we will be. You can find this strand we’ll weave together in the Historical category. Without further ado…

Let’s weave a story, beginning with a country. We’ll call this country Nigeria.

I know what you’re thinking. Why would we be starting with Nigeria if it’s Ghana we’re discussing? I love it when you ask meaningful questions! I’ll use this as an opportunity to emphasize how interconnected each of our diasporic histories are. We’ve always existed in liminal spaces, in webs of events that impact all of our individual identities now and then. For example, if you’ve grown up in West African circles, you’ll be familiar with Jollof Wars, a (sometimes friendly) competition between Nigerians and Ghanaians over which country produces the best tasting jollof. As a Nigerian, I’m partial to Nigerian jollof, but it begs the question: how do these two countries with separate, complex cultures share a renowned dish? We share so many aspects of identity because Nigerians and Ghanaians inhabited the same neighborhoods not too many years ago.

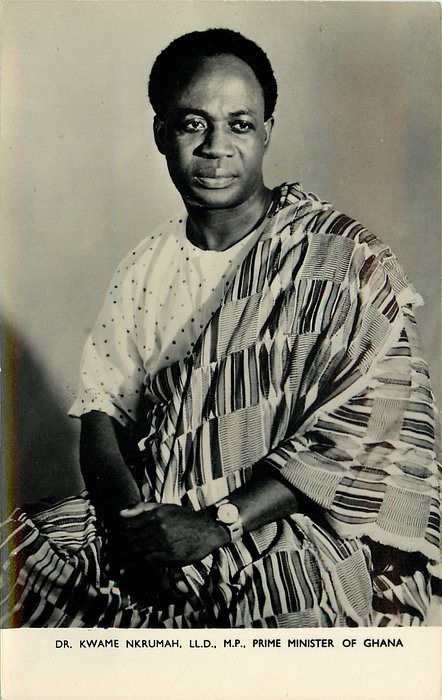

In the year 1958, just a year before my father was born, Nigeria struck oil, making it a commercial epicenter wherein the likes of Chevron and Shell established footholds in drilling contracts. On the cusp of an independence that would follow just two years later, there was money flowing into Nigeria’s economy, enticing to many. Naturally, people from neighboring countries saw the benefit of relocating and settling, particularly a multitude of Ghanaian immigrants who journeyed across a few borders to chop Naija jollof. It only made sense after all. Though Nigeria was experiencing its most prosperous years, Ghana’s economy reflected quite the opposite. Famine and insurgency plagued the country subsequent a crash in cocoa prices and a coup that usurped the first Ghanaian president, Dr. Francis Kwame Nkrumah. Taking advantage of Ghana’s economic instability, Nigerian recruiters corresponded with Ghanaian citizens for the opportunity to relocate east in exchange for the occupation of menial labor jobs that Nigerians declined to fill. By the 1980s, more than two million West African nationals lived in Nigeria, more than half of them Ghanaian.

Like every good era, Nigeria’s prosperous oil boom soon came to an end. In 1982, the oil industry underwent a steep decline as consumer markets slipped into recession and demand faltered. Barrel prices dropped and large consumers like the United States began producing oil domestically, further decreasing the need for imports. As Nigeria’s economy was predominantly dependent on the oil industry, it experienced major hits. It took mere months for the bulk of Nigeria’s foreign reserves to deplete. Food prices surged while salaries made a counter-current. In panicked response, Nigerian officials released propaganda alienating non-Nigerians, particularly Ghanaians who encompassed a large majority of the immigrant population, and blamed them for the 180 degree turn in economic conditions. Soon enough, xenophobic sentiments spread and left Ghanaians vulnerable, susceptible to harassment and abuse.

On January 17, 1983 the first democratically elected Nigerian president, Shehu Shagari, publicly ordered the expulsion of two million immigrants from the country. Many speculate that the ordinance was in response to the 1969 expulsion of an estimated 2.5 million West African immigrants from Ghana, majority of whom were Nigerian, by then Prime Minister Kofi Abrefa Busia, known as the Aliens Compliance Order, citing xenophobic motivations. On the contrary, Nigerian leaders maintain purely economic reasons for the doctrine though many quote government officials stating that the deportations were “inevitable.” Nonetheless, West African nationals were given the abrupt deadline of January 31st to have packed and gone from their homes for the past two decades. So they took all they owned and filled woven plastic, checkered bags of all sizes to the brims and hauled them to the Benin border. While these bags had already surged in popularity before this historic event, they earned the name Ghana Must Go bags due to their reliability and usability at the time.

Despite the solidity of the acclaimed bags, chaos ensued at the borders. Millions spilled into any exit they could access–from the north at Benin, the west at Shaki, and down south at Seme in Lagos, where many perished in stampedes. Military officials ordered the closing of the Nigerian border at Togo with hopes of discouraging coups, which incited Togo to close its border with Benin to offset a refugee crisis. West African nationals exiled from their homes found themselves cornered where they stood with what they could carry in their bags at the borders, in torrid weather sans water. Soon, disease became rampant and the media spread word of the gruesome event like metastasis. The international community condemned Nigeria’s treatment of immigrants and declared a humanitarian crisis, inducing the United States and The Red Cross to dispatch airlifted aid. The impasse ended months later once Ghana reopened its borders and deployed ships to alleviate the number of those traveling by road.

In 1985, only two years later, then-president General Muhammadu Buhari initiated a second mass deportation of African Nationals residing in Nigeria, whether legally documented or not. More than 700,000 immigrants were forced from their homes… again. This act sullied relations between Ghana further as the wound from the previous expulsion was still fresh. Economic relations would never fully recover.

Today, Ghana Must Go bags carry not only a historical significance, but also a heavy weight in African fashion. Traveling home to Nigeria, my family and I are greeted by arrays of colors and prints, not limited to vintage checkered patterns, that adorn Ghana Must Go bags throughout the airport and the markets. The bags have established themselves as a pinnacle of West African fashion and society, serving as a staple in many Nigerian and Ghanaian closets respectively, mine included. With its continuous evolution, Ghana Must Go bags have been ingrained into art and transformed from a grave reminder of a tumultuous history into a symbol of regional pride.

Like many facets of culture, the Ghana Must Go bag represents a turbulent history between two countries, juxtaposed by its colorful symbolism nodding towards the future. From economic turmoil and othering grew a motif that unites two West African countries in the midst of many diasporic wars, including those involving a delicious dish of tomato and rice, that seek to divide them. Ghana and Nigeria remind me of sisters who fight over their differences only to be united by the least expected relic. Unfortunately, neither country has issued apologies or reparations for the tit-for-tat deportations and civil unrest caused by the other.

Though not interchangeable, the histories that shape our identities are interconnected and it is necessary for us to understand one to interpret the other. For a narrative story navigating family dynamics subsequent Ghana Must Go, read the engaging novel by Ghanaian-Nigerian writer Taiye Selasi, Ghana Must Go. Thank you for reading.

Please like and share below. Comment your thoughts and share historical events you think we should discuss here on the Braid Blog!

Join the conversation!