I’d say let’s weave a story, but I’m unsure where to begin. In 1619 with enslavement? In 1863 with Proclamation 95? Or perhaps, we should start in 1865 with Juneteenth? Reconstruction from 1865 to 1877 might be an adequate starting point, too…

Let’s just begin with a holiday. Let’s call it Labor Day.

Labor Day is framed as a celebration of fair wages, shorter hours, and safer conditions, but long before the first official parade marched down New York’s streets in 1882, Black people were already fighting, striking, and organizing for the dignity of work, and long after that parade would the plight for equity endure. Welcome, reader, to a story that sits beneath the smoke of barbecue grills and the flutter of American flags every September.

Our labor story doesn’t begin with the Industrial Revolution. It begins in the fields and shipyards, where enslaved and newly freed people demanded more than survival; they demanded fairness. In 1835, Black caulkers at the Washington Navy Yard led one of the nation’s earliest labor strikes, refusing to be underpaid for their skilled craft (Fridy).

When white unions barred us, we built our own. The Colored National Labor Union, founded by Isaac Myers in 1869, became the first national union for Black workers, forcing the nation to see what solidarity looked like on our terms (Santi). Let’s not forget! Black women have always been at the forefront of labor organizing, even when doubly excluded by race and gender.

For Black women, labor movements were never about securing the “right to work”—that was already a fact of our existence. From the plantation to domestic service to the washerwoman’s bucket, Black women’s labor was never optional, never protected, and rarely valued. So our demands in the labor movement looked different. We weren’t asking for entry; we were demanding equity, dignity, and pay that matched the worth of our work. Take the washerwomen of Jackson, Mississippi and Atlanta in the 1880s, who organized strikes for fair wages and working conditions. With letters to mayors and calls for collective action, they set a precedent: even the most “invisible” labor could shut down a city if it refused to be exploited. Their courage lit the way for future domestic workers and laid the foundation for Black women’s labor activism across generations (Fridy).

Consider Lucy Parsons who led over 80,000 people in Chicago’s May Day march of 1886, demanding the eight-hour workday (Fridy). A woman who was never supposed to stand at the center of labor’s struggle instead became one of the most dangerous women in America in the eyes of the powerful. Parsons later stood as the only woman to speak at the founding conference of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), proving that her radicalism was more than a moment; it was a movement.

This thread continues into the 20th century with leaders like Hattie Canty, the Las Vegas domestic worker turned union president who organized the longest strike in U.S. history, seven years of unbroken solidarity (Fridy). Her fight was the fight of Black women through the centuries: not to gain a seat at the table, but to force the table to be rebuilt in the name of justice. From washerwomen and seamstresses to activists and organizers, Black women defined what labor feminism could look like. While mainstream feminism rallied around the right to work Black feminist movements recognized that the right was already there; the battle was for respect, equal pay, safe conditions, and recognition that Black women’s labor had always been the scaffolding holding up American industry.

Then came the Pullman Porters. After the Civil War, George Pullman hired formerly enslaved men to staff his luxury railcars, stating that formerly enslaved men would cater to the whims of his customers as they were trained to be “perfect servants”. They worked 400 hours a month with little rest, endured constant racism and disrespect, and were paid the lowest of all rail employees. Yet, they became quiet revolutionaries. Porters carried not only luggage but also radical ideas, blues records, and newspapers from city to city, sparking political awakenings that fueled the Great Migration.

By 1925, under A. Philip Randolph’s leadership, they formed the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first Black-led union to win recognition 12 years later in 1937. Their victory proved that Black workers could bend even the most rigid industries toward justice (“The Pullman Porters”). Still, the laws written in Washington cut us out. The New Deal labor protections of the 1930s—Social Security, the Fair Labor Standards Act, the National Labor Relations Act—deliberately excluded agricultural and domestic workers, jobs overwhelmingly held by Black people (Cassedy). That exclusion wasn’t an oversight. It was a design, locking Black workers out of the very safety nets our labor had built.

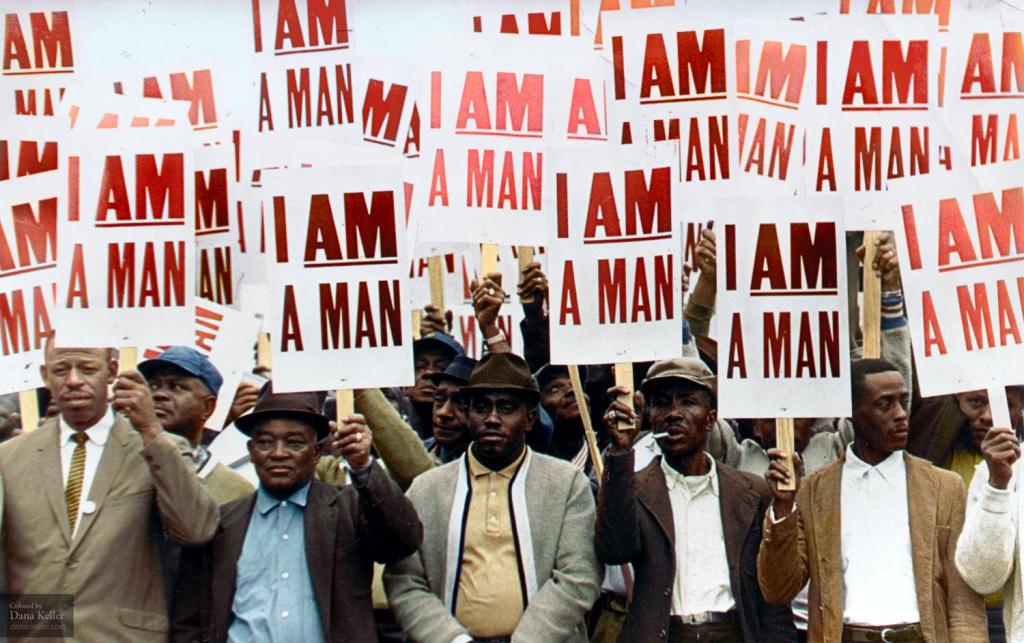

Reconstruction had promised progress, but as Jim Crow swept in, the fight for fair labor morphed into another battlefield of segregation. Solidarity between Black and white workers flickered, as it did during the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 when they marched together in Louisville. By the 1890s, unions like the American Railway Union openly refused Black members, showing that racism outweighed collective interest (Fridy). Once again, we built our own organizations, against the tide of exclusion. Our labor legacy did not stop at union halls. It marched with Martin Luther King Jr. in Memphis in 1968, where he stood with striking sanitation workers who carried signs that declared the most basic truth: I AM A MAN.

Today, about 14% of Black workers are unionized—more than any other racial group—and unionized Black workers earn on average 16% more than those without protection (Fridy). So when we talk about Labor Day, let’s be clear: the holiday wasn’t built for us, but by us. Our hands laid its foundation in shipyards, kitchens, cotton fields, and railcars. Our organizing birthed movements that reshaped the country, even when our names were scrubbed from the textbooks. The call, then, is this: Black workers today must reclaim the tradition. Unionize. Organize. Demand not only better wages, but equity and protection in industries still profiting off our labor. Reconstruction showed us how fragile progress can be, Jim Crow showed us how quickly it can be undone, but solidarity shows us how strong we are when we move as one.

This Labor Day, I remember not just the parades, but the strikes, the washerwomen, the porters, the sanitation workers. The ones who carried more than work; they carried a vision. Now, it’s ours to keep carrying forward. Our ancestors made sure Labor Day was not just about rest, but resistance. This year, may we honor them not just with a day off, but with a commitment to keep organizing, keep building, and keep carrying the torch they lit. The stories I’ve shared here are merely a fraction of the work completed to achieve equitable labor conditions for Black Americans, and may those forgotten and unrecorded victories be honored through the futures of Black laborers all over the world. Thank you for reading.

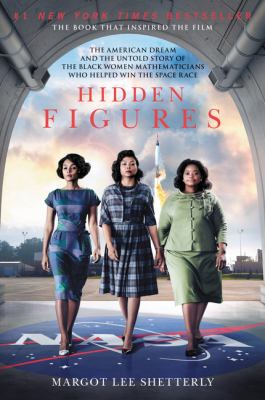

Below I’ve curated a shelf of literature dedicated to historical Black labor movements. Please feel free to peruse and envelope yourself in a history that solidifies our status in this country. Like, share, subscribe, and comment to expand our conversation.

Sources:

Cassedy, James Gilbert. “African Americans and the American Labor Movement.” National Archives and Records Administration, National Archives and Records Administration, http://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/1997/summer/american-labor-movement.html. Accessed 31 Aug. 2025.

Fridy, Emma. “A Short History of Black Labor Movements in America.” The University of Louisville’s Premier Non-Partisan Student Publication, 10 Feb. 2023, loupolitical.org/2023/02/10/a-short-history-of-black-labor-movements-in-america/.

“The Pullman Porters.” History.Com, A&E Television Networks, 27 May 2025, http://www.history.com/articles/pullman-porters#Rise-of-the-Pullman-Palace-Car-Company.

Santi, Christina. “How Black Workers Shaped the History of Labor Day.” Waymaker Journal, 2 Sept. 2024, http://www.waymakerjournal.com/black-workers-history-of-labor-day/.

Join the conversation!