Welcome, Braid-y Bunch, to the first limited series in our strand of history, We Wuz Kangz! I am delighted to embark on ancient African history we’ve known since elementary–but haven’t truly known. As a Twitter enthusiast, I had to use this hilariously popular phrase to describe a sequence of accounts detailing the daily lives our ancestors lived in ancient Africa. In anticipation…

Let’s weave story, beginning with a continent. Let’s call this continent Africa.

So, yes we were kings–a few of us, at least. Most of us were farmers, priests, smiths, soldiers, artisans, and merchants, however, who lived normal lives similar to how we live today, but that doesn’t make us any less remarkable. The working class, much like today, were the economic backbone of African society, pioneering advancements in art, technology, religion, etc. that could not exist without their significant contributions. Let’s start from the beginning of our story as we are getting a bit ahead of ourselves.

Travel with me to 3100 B.C.

Now the Lord God had planted a garden in the east, in Eden; and there he put the man he had formed.

Genesis 2:8 NIV

Africa as we know it today was much different in ancient times. When civilization began sometime around 3100 B.C., the continent was known as Alkebulan, meaning mother of mankind or garden of Eden. Records of African history note that civilization began in Egypt, the northeastern country home to Pharaohs and the pyramids–where neolithic communities participated in trade and farming. So, before we dive in, let’s make it very clear that Egypt is African. It may have been conquered by Arabs in 614 A.D. but native Egyptians are Black people despite propaganda that would like to convince us otherwise.

Life in ancient Egypt wasn’t just about toiling fields and erecting monuments. In fact, Egyptians lived immensely full lives, engaging in sports, festivals, literature, and quality time like we love to do today. Life, in fact, was so absolute that they believed the afterlife was an even more beautiful extension of life on earth, which is why Egyptians exercised such a profound reverence for the dead. We learned in school about their embalming processes and tombs that housed mummies wrapped in natron, a drying salt-like substance, and linens to preserve the body. In addition, the dead were adorned with amulets and other riches to accompany them into the afterlife, as well as prayers and magical scriptures enscribed on their linen wrappings to bless them along their journey to the afterlife. The adorned and encompassed bodies were then placed in beautifully decorated coffins, sealed with resin to avert moisture, and locked behind the massive doors of an equally, if not more, secure tomb within the depths of the famous pyramids.

The pyramids are monuments dedicated to the Egyptians’ affinity for life. Kings and queens found their final resting places within its reliable walls, a constant reminder of their names and stories. Their triangular shapes symbolize the rays of the sun and were designed to assist the deads’ souls in their ascent to heaven. Because of their representation of divinity and enlightenment, the upheaval of the pyramids was left to the artisans and architects, experts in their fields who were compensated handsomely, as opposed to the popular belief that enslaved people were the primary builders.

Predynastic Period (c. ~6000-3100 B.C.)

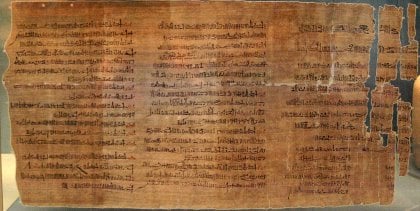

The time before recorded history from the Paleolithic to the Neolithic age. Scholars rely on the chronological recording of an ancient Egyptian scribe named Manetho who wrote Aegyptiaca, a history of Egypt, in the 3rd century BCE. Unfortunately, the scribe’s manuscript has been lost and we must now rely on the works of later historians for records. That being said, most ancient historical information are approximations based on archaeological data.

Chattel slavery did not originate in the motherland…

Now, on the subject of slavery in beginning in Africa, let’s set one thing straighter than a fresh relaxer. Chattel slavery did not originate in the motherland, contrary to American propaganda. Criminals, the indebted, and prisoners of war were enslaved and subjected to a lesser quality of life than Egyptian citizens, but there was no ethnic designation for slavery, nor were the enslaved mauled, beaten, raped, or dehumanized. They were even compensated and offered the opportunity to regain their freedom, depending on the circumstance.

In fact, Egyptians made it a priority to live happy lives and partake in sharing joy amongst themselves. Children were raised communally by women in communities and received advanced practical educations, while men and women were hunters and gatherers, trading game for agriculture, and dispersing wealth within their ranks. This sounds just like the canonical Black community to me and like the canonical Black community, they endulged in religious practices much different from what we know religion to be today. If you’ve watched five minutes of Disney’s Prince of Egypt, you know that Egyptians believed in magic and practiced polytheism, the worship of multiple gods. Heka, it was called–their magic that predated the gods and was the underlying force for their divine power.

Heka

An attribute of the Egyptian god Re (Ra), the god of the sun who was regarded as a creator and sustainer of life.

Heka was the source of power for more than 2,000 Egyptian dieties including Isis, the mother of all Pharaohs; Osiris, lord of the underworld and judge of the dead; Horus, god of the sky; Amun, god of air; Thoth, god of writing, magic, wisdom, and the moon; and Anubis, god of mummification, funerary rites, guardian of tombs, and guide to the afterlife–to name a few prominent cult deities. These gods are well-known in history but there are thousands as the number is not fixed. If anything, there was somewhat of a revolving door of deities; new forms appeared while others were forgotten and ceased to be worshipped.

Nonetheless each deity had manifestation forms, most commonly in animals, or grotesque animal combinations, or other aspects of nature. The animal was meant to represent the essence of the god with many fierce goddesses were emblematized as lionesses, and the mild were smaller cats. The more popular gods, like the aforementioned bunch, chiefly had human forms like the fertility god, Min. Followers of these gods, communally referred to as cults, erected temples designed for the daily tending and worship of its deity, which emphasized the importance of temple worship. Though temples were primarily microcosms for specific gods, the worship of smaller gods within the order of the principal god was essential and because these gods may not have had a human manifestation, they were depicted with their representative animal’s head and a human body, pertinent to decorum within the temple. These temples, and their cults alike, were a state concern as the Egyptian government were convinced of their necessity to maintain reciprocity between humans and the divine. Similar to Christian practice, ancient Egyptians carried offerings and gifts to temples to appease and petition the gods. With the increase in these practices, priesthood increased equally, if not more, in importance, warranting the establishment of full time professional priest positions within temples.

What parallels do you notice between religious practices in ancient Egypt and religious practices today?

Despite the evolution and popularization of these religious practices, evidence does not support mass temple worship, so it didn’t quite resemble our modern mega churches. Most people were resolved to local sanctuaries that responded to the niche concerns and needs of its surrounding community. It seems that the majority petitioned the recently dead for assistance with their troubles, as required by customs–though they reverenced gods in their own right. These petitions, written letters containing details of their issues and requesting help, were accompanied by offerings and brought to the shrines of the dead. This practice, however, was primarily confined to a small population of literate people.

I know what you’re thinking–what do you mean a small population of literate people? Remember that temples and priests were protected and respected by the state as they were essential to maintaining equilibrium between gods and man. Well, because they were so instrumental to order, education was part of that order and because temple worship was not widespread, many people rejected formal education in favor of learning practical skills in the home encompassing agriculture, engineering, and sculpture. As a result, many people could not read or write very well.

Despite the limitations on literacy, ancient Egyptian society was extraordinarily innovative, building tools and systems that still ripple through time. They invented bronze, a harder alloy of tin and copper, by 3000 BC, ushering in the Bronze Age with stronger weapons, tools, and armor. They broke ground in writing itself, birthing hieroglyphics–a blend of logogram, syllable, and alphabetic systems of nearly a thousand characters–and passing that script lineage forward into Greek and Aramaic alphabets. Then there’s papyrus, birthed from the river’s pith, transformed into scrolls that preserved history, like letters describing the final years of the Great Pyramid’s construction discovered at Wadi al-Jarf. Without ink, those scrolls would’ve been silent; Egyptians mixed soot, gum, and beeswax into black (and later red) inks to bring words to life.

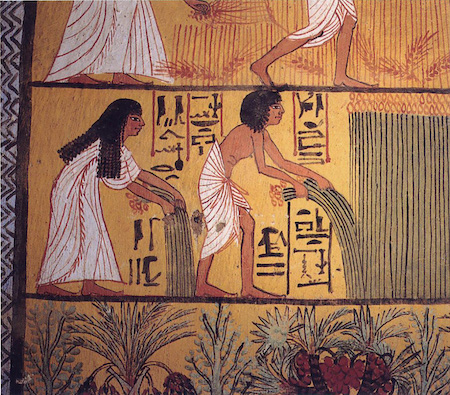

The fields thrived under ox-drawn plows and curved sickles, simple bronze tools that revolutionized agriculture. Their ingenuity didn’t stop there: they mastered irrigation, building canals with gates and reservoirs, and used the shadoof, a lever-and-bucket water system, to move Nile water across fields with precision. They mapped time, too, tracking when Sopdet–a star that signaled the annual flooding of the Nile–reappeared to create a 365-day solar calendar, twelve months long, later corrected for the missing quarter-day by including a leap-day. Architecture and measurement were no less refined: water clocks, corbeled arches, early glass-making, even furniture with use and elegance. Inside tombs we see surgical skill: scalpels, bandages, swabs, even gynecological tools drawn in the Edwin Smith Papyrus, a 1600 BC medical manual that outlines diagnoses, treatments, and prognosis.

Egypt pioneered many advanced feats, which is why the country is consistently separated from Blackness and conversations surrounding Africans. It damages the colonial agenda to circulate the fact that creators had dark skin and wooly hair, but we know better than that. Each of these inventions were fathered by mundane Africans living in ancient Egyptian–everyday insignificant inventors whose names many of us don’t remember. We remember kings for their names, but we honor invention for its mark made on history, even more than 4000 years later. Everyday Africans are the reason we have so much technology today, contrary to western propaganda, and it’s how we ought to identify without the need for respectability politics. Egypt’s prosperity influenced the makings of many ancient European societies; never forget that we were the first. We never needed to be kangz to be important, to be worthy of life. We wuz engineers, authors, priests, farmers, merchants, smiths, inventors–like we are today. Thank you for reading.

Return Monday, October 20th for the second leg of this series featuring The Benin Kingdom.

Please like, comment, subscribe, and share to expand our conversation.

Citations

Mark, Joshua J.. “Predynastic Period in Egypt.” World History Encyclopedia. World History Encyclopedia, 18 Jan 2016, https://www.worldhistory.org/Predynastic_Period_in_Egypt/. Web. 02 Jul 2025.

Badawi, Zeinab. An African History of Africa: From the Dawn of Humanity to Independence. Mariner Books, 2025.

Baines, John R., Dorman, Peter F.. “ancient Egyptian religion”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 11 Jun. 2025, https://www.britannica.com/topic/ancient-Egyptian-religion. Accessed 8 July 2025.

Arnove, Robert F., Moumouni, Abdou, Nakosteen, Mehdi K., Riché, Pierre, Ipfling, Heinz-Jürgen, Vázquez, Josefina Zoraida, Huq, Muhammad Shamsul, Chambliss, J.J., Browning, Robert, Meyer, Adolphe Erich, Chen, Theodore Hsi-en, Scanlon, David G., Shimahara, Nobuo, Bowen, James, Marrou, Henri-Irénée, Mukerji, S.N., Thomas, R. Murray, Anweiler, Oskar, Graham, Hugh F., Swink, Roland Lee, Naka, Arata, Lawson, Robert Frederic, Szyliowicz, Joseph S., Lauwerys, Joseph Albert, Gelpi, Ettore. “education”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 3 Jul. 2025, https://www.britannica.com/topic/education. Accessed 8 July 2025.

Wendorf, Marcia. “Ancient Egyptian Technology and Inventions.” Interesting Engineering, 23 Apr. 2019, interestingengineering.com/lists/ancient-egyptian-technology-and-inventions.

Join the conversation!