Let’s weave a story, beginning with an author. Let’s call this author Esmeralda Santiago.

Esmeralda Santiago is a native of Puerto Rico. She grew up in a rural town before moving to Brooklyn, New York with her family at thirteen years old. As the oldest of eleven siblings, she was responsible for not only her own assimilation, but for ensuring her siblings had a positive role model for braving their new environment. Her family was poor and disenfranchised, and though she experienced

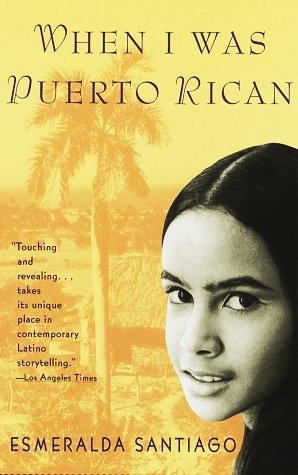

years of hardship, her writing was born as an outlet for all the feelings she didn’t have words for then. Despite her humble beginnings, Santiago graduated Magna cum Laude from Harvard University, earned an MFA in creative writing from Sarah Lawrence College, and has been awarded Honorary Doctorates from five universities. She has served on the boards of The Jacob Burns Film Center, the Scholastic Art and Writing Awards, the PEN American Center, and The National Museum of Puerto Rican Arts and Culture. Her transcultural experiences were the catalysts for her collection of groundbreaking publications, including her coming-of-age memoir When I Was Puerto Rican (1993), which transports us to the 1950s–before Puerto Rico became a U.S. territory.

“It seemed too complicated, as if each one of us were really two people, one who was loved and the official one who, I assumed, was not.”

Esmeralda Santiago, When I Was Puerto Rican (1993)

The memoir follows four-year-old Neji whose family has just relocated to Macún, Puerto Rico. Neji is the oldest of three with two younger sisters by names of Delsa and Norma. The first things Neji begins to recognize are her relationships with her parents, Mami and Papi, and their relationships with one another. She is drawn to her father, always wanting to spend time with him in his work shed–helping him pick up nails as he restores the floorboards of the fixer-upper home they moved into is one of her favorite activities. She grows into this personality, avoiding the kitchen and domestic responsibilities Mami tries to goad her into. She grapples for Papi’s affections and resents having to share him with her sisters.

The first time Neji identifies herself, it’s as a jíbara, meaning a person from the country. The area they lived in was rural, as was her grandparents home, and she recognized that they lived like jíbaros. Nonetheless, Mami does well to stifle that association, reminding Neji that she can’t be a jíbara because she was born in the city, where that class of people are disparaged. Like any child, Neji questions this but hardly receives any answers.

When Mami gives birth to Héctor, Neji finds herself navigating new emotions, including jealousy because she feels that another baby will put more distance between her and her parents. She and her sister already sleep in hammocks, a curtain dividing their side of the room from her parents’, and she wonders how the new baby will fit into the home. Tension was already observed between Mami and Papi, but intensifies greatly after Héctor comes into the picture. Neji overhears her parents’ arguments in the one-bedroom home and fails to understand the way Mami accuses Papi of infidelity and dishonesty. Soon enough, she learns of Papi’s other daughter, Margie, and longs to meet her. Papi informs her that the outside daughter and her mother have relocated to New York and struggles with emotions surrounding the revelation. Despite the quarrels, Mami becomes pregnant again and Neji falls deeper into despair.

Eventually, tensions grow severe and Mami gathers her children and relocates to San Juan, Puerto Rico. Starting first grade in the city, Neji begins to notice differences between she and the other childrens’ social classes–their clothes, the vehicles their parents drive, and their dignidad, or manners. Her classmates tease her for being a jíbara and she ends up in multiple fights as a result, understanding the term as negative instead of what she hoped it to be. After Mami gives birth to baby Alicia, Papi comes around more often and soon enough, the family moves back to Macún.

“I would just as soon remain jamona than shed that many tears over a man.”

Esmeralda Santiago, When I Was Puerto Rican (1993)

The book’s fourth chapter ushers in a new era–the American invasion of Macún. At school, Neji is introduced to English and is forced to sit for vaccinations she’s never heard of. She learns new words like ‘imperialist’ and ‘gringo,’ which Papi warns her never to use with white people, but she learns that the Americans are called that because of their mission to change Puerto Rican culture and force its natives to assimilate to their culture. Her father gives her examples of slurs, and shares that Americans use them to degrade Hispanics. Neji vows never to learn English so she does not become like the foreigners who implement new processes at her school. Between learning more disparaging terms like puta and jamona and watching as men catcall Mami in the street, Neji begins grappling with society’s treatment of women, and is angry with what she learns. These feelings are further amplified when Mami gets a job at the newly opened factory following increased economic hardship caused by Hurricane Santa Clara–one of the first women in Macún to do so, which earns her exile from neighboring families. Even Neji’s friends seem to abandon her.

Womanhood continues to rear its head as Neji experiences an uncomfortable situation with a family friend named Don Luis who tutors her in piano–when she finds him peeking down her shirt at her developing chest. She learns about sex after a neighborhood boy exposes his genitals, horrified and disturbed at the details. Though these and Papi’s treatment of Mami wither her perception of men, she finds solace in soap opera characters who dote on fictional women and wishes to experience a similar affection. Before her thirteenth year, Mami relocates her and her now six siblings to Brooklyn, New York, where she meets her first crush, Johannes. She compares him to the men in the soap operas and decides he isn’t good enough, ending the relationship.

“They think we’re taking their jobs… There’s enough work in the United States for everybody, but some people think some work is beneath them.”

Esmeralda Santiago, When I Was Puerto Rican (1993)

Neji struggles to understand social dynamics at her new school. Children of like races and ethnicities form cliques and fight one another constantly. She learns from her classmates American sentiments toward Hispanic immigrants but she works hard to learn English, nonetheless, to survive eighth grade. Assimilating to this new divisive culture while assuming responsibility of her siblings proves difficult. Experiencing misogyny only adds to her stress. She finds herself confused when her uncle squeezes her nipple, then gives her a dollar; and when a random man in a parked car smiles at her while masturbating. The start of her period is another hurdle of confusion added to her list. Her family’s economic status improves but is disconcerted when Mami is laid off and they’re placed on welfare, which she learns also carries a negative connotation. She works hard at school despite external struggles, with hopes of becoming an actress. After stumbling over English words performing a monologue during an audition for the Performing Arts School in Manhattan, Neji falls into despair. She fears she’ll never make it out of Brooklyn.

Throughout the memoir, Neji matures into a young woman gaining broader understanding of the world around her. From the moment she becomes curious about her identity, she never ceases to try to understand who she is–as a person, as a girl, and as a Hispanic in America. From her mother, she learns the kind of woman she desires to be: resilient, independent, and unrelenting; and from her father and the disgusting men around her, she learns the kind of man she shouldn’t associate with. When I Was Puerto Rican guides readers through the eye-opening timeline of girlhood, from untapped innocence to unbidden awareness through the eyes of a brown girl who had more to digest than just growing up. Neji’s story mirrors the lives of many little Hispanic girls who must navigate torrent landscapes of youth and identity. It shines light on both the economic and social disparities present in Hispanic communities, especially surrounding young girls who should be guided and protected. Esmeralda Santiago’s When I Was Puerto Rican is a must-read for its historical relevance and relatability to first-generation American children who must helm both assimilation and maturation. I know many first daughters who share stories similar to Neji’s and I couldn’t help but empathize as I turned each page. Santiago amplifies their voices, healing inner children who once had no voice. Thank you for reading.

Please like, comment, and share to expand our conversation; and subscribe to The Plait for biweekly newsletters delivered directly to your inbox. Immerse yourself between the lines of such a thought-provoking novel, and click the links below to visit Santiago’s socials and explore transcultural experiences through her array of memoirs.

Join the conversation!