Let’s weave a story, beginning with a director. Let’s call him Spike Lee.

Shelton Jackson “Spike” Lee is a highly decorated filmmaker, actor, and regarded auteur from Atlanta, Georgia. He is known for his prolific and influential interpretations of race relations, issues within the black community, the role of media in contemporary life, urban crime and poverty–to name a few, and has won far too many awards to count. Founder of Forty Acres and a Mule Filmworks, Lee has directed over thirty-five movies, but has had a hand in north of fifty-three productions including She’s Gotta Have It (1986), which was his directorial debut; Do The Right Thing (1989); Malcolm X (1992); and his highest-grossing film to date, Inside Man (2006). As an artistic pioneer and inherent social justice connoisseur, Spike Lee has engrossed viewers

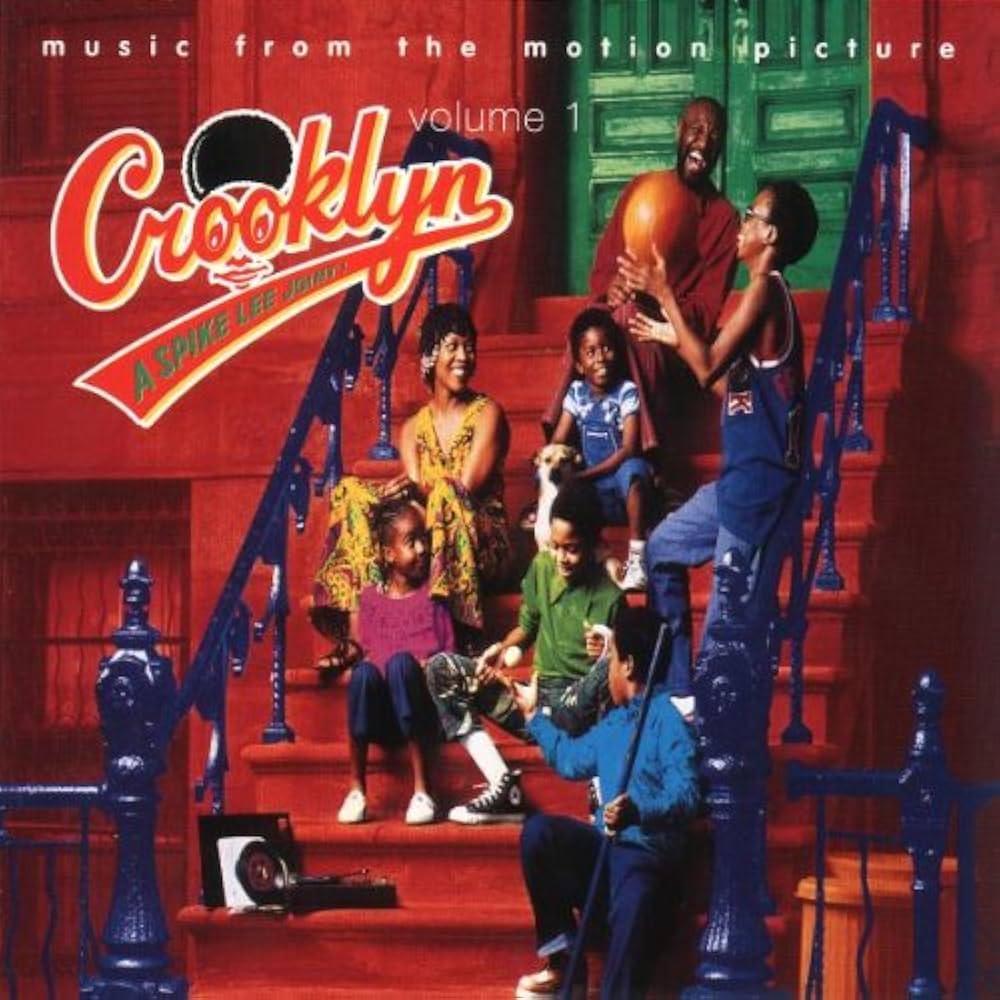

with exhilarating plots to dissect and expose socioeconomic disparities within African American communities. Equally entertaining as they are provocative, Lee’s films spark conversation around phenomena normalized in Black households. Our conversation will dissect the Black household depicted in his film Crooklyn (1994).

This conversation is especially important to me because this movie centers a young girl named Troy, the only daughter in a family of four sons. Now, if you know you know where this is going. As the only girl in the home, Troy is saddled with a majority of the household responsibilities despite being the fourth child. Her mother, Carolyn, runs the home without much help from her father, Woody, financial or otherwise, and her brothers, divide their time between running amuck, fighting over the television in Troy’s bedroom, and disrespecting their mom.

Woody: People are gonna come to this concert. People still want to hear good music. I don’t give a damn how many records this rock ‘n’ roll shit sells. People know the difference between that and good, pure music. I need you to support me in this, Carol.

Crooklyn (1994)

Carolyn: Oh, looka here. Who gets up at the crack of dawn, Monday through Friday, cookin’ breakfast, go to school, teach school, come home, cook dinner, grade papers, make lesson plans, try to keep our rowdy kids from killin’ each other and destroyin’ our house, just so you can be a “pure” musician playin’ “pure” music? If that ain’t support, I don’t know what the hell – what is.

The very first thing I noticed in Troy’s story is her independence at such a young age. In her environment, she was forced to mature prematurely. Our protagonist was seen walking to bodegas late at night on her own to purchase groceries for herself. In the midst of her lonely travels, she’s witnessing arrests and mayhem, drug dealers and glue sniffers, and gang activity and crime. My first thought was, “why is that baby outside by herself… especially when she has four brothers?” No one blinks an eye at her sneaking out of the house, which further illustrates the mundanity of her hyper-independence. This likely stemmed from watching her mother be the sole provider of their household. You read that right. Yes, Woody, their father was present but Carolyn was what I call a married-single mother. Carolyn worked hard as a teacher to put food on the table, only for Woody to spend the family funds on this struggling music dreams. So much that he wrote five–yes, FIVE–bounced checks without his wife’s knowledge, and initiated an argument when she confronted him about it. Not only was he a financial leech, he didn’t even help with the children. He wasn’t parenting; he was assuaging the kids instead of enforcing the rules their mother put in place. This offered their sons the comfortability to undermine Carolyn constantly, especially their oldest, Wendell, who incessantly back-talked and disrespected her because the father figure of the house did not set a proper example. Instead, Woody would bring home treats so the kids didn’t recognize him as the “bad parent.” So many Black households lack proper male representation, stemming all the way back to slavery and emancipation. By continuing his behavior, Woody perpetuated a cycle of misogyny by teaching his sons that it’s okay to disrespect women. It’s why they treated Troy the way they did, but we’ll get to that soon.

Then Woody had the nerve to bring Troy into his ploy to reconcile with Carolyn. As a child who naturally assumed responsibility to help her mother, this became yet another weight on her shoulders. Because of these many stressors, Troy does well to make herself small to accommodate the burden her mother has with her siblings and father. Nightmares about turning into the addicts and decrepit characters in her neighborhood manifest, and so did bedwetting and sleepwalking, which are well-known indicators of high stress in children.

But many out-of-the-ordinary phenomena were pretty much normalized in the Carmichael family’s day-to-day, and when I say “out-of-the-ordinary” I mean completely one-hundred percent ordinary for Black families in the hood but not-so-ordinary in what you’d expect children to be exposed to. Spike Lee took delicate care to depict this in a way that conveyed the laissez-faire attitude towards it but still amplify the effects this rearing has on young children.

Son of a bitch. I can’t even enjoy my meal without that funky McNasty f*ggot ruining my appetite.

Woody, Crooklyn (1994)

In their culturally mixed Bed-Stuyvesant neighborhood, there is gross homophobia, covert anti-Blackness, and unaddressed misogynoir. It’s one thing to call out a neighbor over their hygiene, but it’s another to assault them because of their sexuality, which is evidently the reason for the altercation between the Carmichaels’ veteran tenant and their homosexual neighbor. The example this sets for the neighborhood children, especially the young boys who look up to this formidable man, is that not only is gayness abhorrent but also that it’s okay to exercise judgment on others’ ways of life because you don’t agree with it. The same can be said of the many displays of misogyny. It creates a trickle-down effect that employs Troy’s brothers to use language like, “flat-chested wench,” when looking to get under their sister’s skin. While many would understand this as the way children play, insults like this towards budding girls lead to body dysmorphia. Dramatic analysis, right? Then why did Troy start stuffing her shirt?

Peanut: Get your hands off me, you coconut West Indian monkey!

Crooklyn (1994)

West Indian Store Manager: Listen you little pickaninny. Get out of my store – and don’t come back here no more! Oh, God, these American children. They don’t know how to act. They have no manners.

Living amongst people of diverse backgrounds meant anti-Black rhetoric was prevalent on the Carmichaels’ block. From bodega owners overlooking little Hispanic girls stealing in favor of suspecting Black children to blatantly racist comments amongst the children like, “ugly monkey,” “gorilla,” and “topsy,” prejudice was another harmful mundane aspect of these children’s upbringing. Even as much as exalting looser hair textures over their own, calling a Hispanic girl’s hair “good hair” and their own “nappy.” Unfortunately, this was not exclusive to Bed-Stuyvesant’s location. When Troy left to live with an aunt in Virginia, her first hair appointment introduced her to the hot comb that was apparently needed to “comb out her naps.” I feel that my readers will see these quotes and think, “That’s nothing. We all heard that growing up.” And exactly, thank you for proving my point. These experiences are normalized in our communities and foster internalized anti-Blackness and self-hate that affects generations past what we understand. The Pan-African and Natural Hair Movements could only scratch the surface of irreparable cultural damage.

Troy’s time in suburban Virginia wasn’t all bad in spite of that simple truth. The version of Troy viewers experienced when she lived with her aunt was, in my opinion, her best-self. A version where she was not witnessing indecency or worrying about fixing her parents’ problems or rough-housing with a gang of boys. She experienced girlhood and sisterhood living with her cousin, even if she had her own issues. This visit served as Troy’s introduction to ladylike manners and religion, two arguably important aspects of Black childhood, especially in girls.

Our brave (but she shouldn’t have to be) protagonist returns to New York only to learn her mother had fallen incredibly ill. I was saddened by the moment, but I was further sobered when Carolyn asked Troy to assume responsibility for her little brother. Troy’s distinct lack of emotion perturbed me above all else, especially after her mother passed. She doesn’t cry. She doesn’t mourn. She has to be strong for her family, as her mother was. She now saw herself as the bearer of that torch. So, she went home, checked all the lights, and immediately started cleaning. It appears that Troy has a sort of stoic grief until she starts thrashing from traumatic dreams and vomiting constantly.

Crooklyn is undoubted a comedy, but might I argue that it’s a tragicomedy? While some parts earned a chuckle from me, others had me digging beneath the surface for their intended message. It’s important we protect little Black children, so they can be just that–children. A lot of them aren’t given the chance to bask in blissful ignorance. They’re forced to mature young and shoulder the responsibilities of their parents or other adults around them. Troy’s story is a cautionary tale because our daughters are often the primary victims of this trauma. The generational trauma cycle can be stopped, but we have to recognize the fallacies in our culture that trap us in never-ending pain. So, yeah, we love the he-he-ha-ha moments in Crooklyn but I think the normalcy of these experiences were the most dangerous part. Exposure to these surroundings had a psychological impact that was imperatively clear, if you looked closely enough. I hope Spike Lee and I weren’t the only ones who did. Thank you for reading.

Please like, comment, and share to expand our conversation. Scroll just a little further to subscribe to The Plait, a newsletter that will keep you braided into each new strand.

Join the conversation!