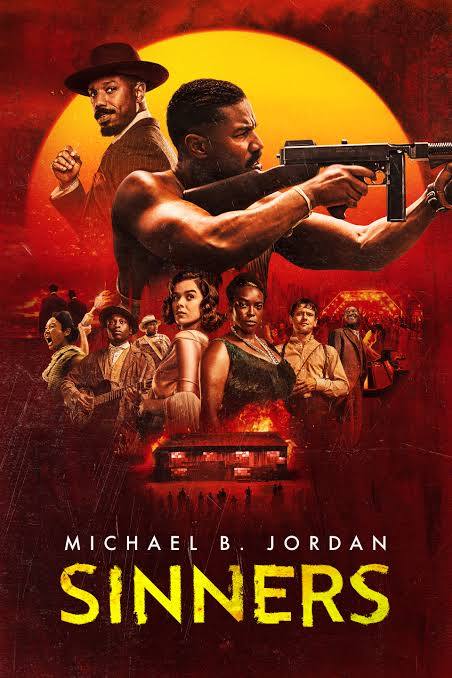

Enough time has passed and the anticipation welling in my chest has finally reached its pinnacle. It’s time we discuss SINNERS by Ryan Coogler–not only for motifs and interpretations, but also for its impact on the Black American community. I can guess what you’re thinking… I thought you discussed books, and while yes that’s true, literacy entails more than physical pages. Media literacy is the ability to accurately analyze motion pictures and songs, both of which will be dissected and consumed on this blog. It’s important to prioritize each in their own respects so that comprehensive literacy may be achieved. You can find this Strand, and those alike, within the Movies & Media category. That being said…

Let’s weave a story, beginning with a character. If you’re familiar, we’ll call this character Sammy.

Sammy, played by actor Miles Caton, is a 20-year-old son of a preacher named Jedidiah living in 1930s Mississippi. His aspirations of becoming a renowned Blues singer are accentuated by his remarkable talent, but belabored by his father’s expectations. In order to understand the sociocultural sentiments towards Blues music, we must first understand social norms of this era.

Blues music emerged in the 1860s, first coined “Delta Blues” due to its soulful roots winding in the soil of the Mississippi Delta.

Inspired by the laments of enslaved African Americans in Negro Spirituals, Blues music explores themes of hardship, injustice, poverty, and struggle during the violence of slavery and its aftermath. Naturally, Blues music became an emblem of resistance, one many did not take a liking to. With its aforesaid themes becoming taboo in the generational tradition of suppressing trauma, coupled with its patronage of unsavory establishments, many Christians divested from indulging in this particular genre and it soon grew in infamy as “The Devil’s Music.” So, our first motif is uncovered in this title: religious manipulation.

“You keep dancing with the devil… one day he’s gonna follow you home.”

Jedidiah, Sinners (2025)

Not only is Jedidiah’s disproval of Sammy’s desires illuminated, we are also given our first foreshadow crumb of the movie. Later in the film, Sammy will wrestle against flesh and blood, looking to escape the grasp of an Irish vampire named Remmick who seeks to pillage his talents under the guise of community and tolerance. Sound familiar? I’m glad it does! Perhaps, you’re calling to remembrance the likes of British and Spanish colonizers who plundered entire African countries under the same false pretense, and with them, they spread Christianity and disease. Paradoxical to a fault, it’s the pressures of Christianity that condemn Blues music and chase Sammy into the arms of a vampire who uses the same rhetoric to justify absorbing that same music. In the same vein, Sammy resorts to reciting the Lord’s Prayer in what he thought were his last moments, Remmick joining in (even as a demonic spirit) to highlight the fallacy in his actions. His Irish identity plays a significant role in the value of Christian belief as the Irish were occupied by the British and subdued under a foreign religious belief system–the same system of beliefs that justified their colonization and displacement. It’d be expected that Remmick would be an ally, in search of identity that was stripped from him, similar to many Black Americans in this time period. Nonetheless, whiteness takes precedence over mutual struggle and Remmick then becomes the oppressor himself–which is a predictable trope seen in many non-Black communities of color.

In complex relationship, Christianity is a double edged sword in the Black community. While it rallied hope in a time fear overshadowed Blackness, it resolves to enslave the minds of those who revere it. Sammy failed to escape the weight of its grasp, while the antagonist weaponizes its message, once used to oppress his own people, to gain power over another group of people already trampled upon by its doctrine. Though Sammy’s aim was to escape the umbrella of Christianity as it threatened the fabric of his identity, he struggled to truly evade its stronghold on so many aspects of his life, much like many of us today navigating relationship with God while grappling with the demonization of threads of Black culture. Even in the resolution of the film when he returns home to the church, he is further condemned by his father and forced, once again, to make a choice between religion and his identity.

Coogler’s choice to portray Remmick as a vampire enhances the metaphor in the danger of allyship. The blood-sucking nature of this mythical creature represents actions taken by other communities to extract the life from Black creations and leave a barren carcass for consumption. His ability to transform characters into extensions of himself and absorb their abilities (i.e. his newfound ability to speak Mandarin after transforming Bo into a vampire) is reflective of the manner in which culture is extracted from its native body, perverted, and discarded by oppressors who indoctrinate the unsuspecting. At the juke joint opened by Smoke and Stack, a pair of twins played by Michael B. Jordan, Remmick and his now-turned-vampire band of Klu Klux Klansmen (ironic, right?), request entry to enjoy the spoils of intonations from Sammy’s guitar, rejecting the option to patronize a slew of white establishments mere miles up the road. Once cast away, another white character–Mary–decides to leave the walls of the juke to negotiate their terms of entry.

“We gon’ kill every last one of ya.”

Mary, Sinners (2025)

Mary is an instrumental character because she is what I call an entitled ally. Having grown up within the Black community but with only a small percentage of Black ancestry, and none that’s immediately visible, Mary experienced an identity crisis that left her teetering the line of Blackness. She desired, however, to cross said line and felt entitled to her right to do so, neglecting the fact that it could easily bring harm to the community she claimed to appreciate. We see this multiple times when she approaches Stack and Sammy during the train station scene, never once stopping to take account that interactions with white women could mean these Black men could be lynched.

In that same scene, she raucously announces the affair she had with Stack, which could have also merited persecution. Repeatedly throughout the film, Mary refers to Black male characters as “boy,” an occurrence that caused viewers to wry in their seats. From her perspective, she means no harm but she doesn’t realize that she is exacting racial violence against them in using a derogatory term that is only endearing amongst members of Black communities, of which she is not truly part. Her ignorance of these nuances show that she may be comfortable in Black spaces, but was not raised to appreciate or accommodate them, only occupy. Mary is important because making the mistake of trusting this archetype is exactly what destroys communities, as properly enunciated in this film. Mary, with the trust she’d gained from patrons of the juke, exposed them to the violence Remmick sought to exact.

Grace is a different ally archetype, one who resides amongst a community of people, but doesn’t consider herself part, rightfully so. However, this leads to apathy and a sense of preservation that sometimes excludes the community she lives in. Now, this is controversial as many people believe Grace did nothing wrong, myself included. She weighed the options and made a choice she felt was best for her daughter and the rest of the town, to the demise of the remaining living in the juke joint. After all, she didn’t attend the grand opening for enjoyment; she hoped to profit from the establishments created by Black people. It’s befitting, nonetheless, as she maintained the shop on the white side of the road, while her husband, Bo captained its equidistant Black counterpart.

The Mississippi Delta Chinese community settled in the Deep South between 1910 and 1930, erecting grocery stores in white and Black neighborhoods in need of small businesses and merchant hubs. Serving both communities and navigating a new racial landscape, Chinese immigrants in the 20th century found themselves with a unique identity between white and Black. They weren’t fully accepted by white people despite their fair skin and were subjected to discrimination specific to their heritage, but they also weren’t alienated by the Black community. Nonetheless, racial tensions persisted but they didn’t shy away from developing close bonds with Black patrons, as we witnessed in Bo’s fondness of Stack, even so much as offering credit and IOUs to customers who couldn’t pay immediately. Despite the formation of these close relationships, the Chinese were still othered and therefore, maintained allegiances to their monoethnic community. Grace properly displayed her allegiance in her final act of love: inviting the vampires into the juke to save her daughter. Never mind that, while this choice may have saved those near to her, it killed the remaining who still had their souls intact.

In the end, the most impactful character proved to be a Black woman by the name of Annie, one of the remaining few who still practiced the remnants of a native African religion: Hoodoo.

“There are legends of people… born with the gift of making music so true, it can pierce the veil between life and death. Conjuring spirits from the past… and the future. In Ancient Ireland, they were called Fili. In Choctaw land, they call them Firekeepers. And in West Africa, they’re called griots. This gift can bring healing to their communities but it also attracts evil.”

Annie, Sinners (2025)

Colonialism’s demonization of African religions allowed for the successful proliferation of Christianity. Libraries of ancient texts, remedies, and practices were pillaged and burned, scattering valuable cultural nuances and further dismantling African identity. Annie’s understanding and practice of Hoodoo is what equipped her fellow characters with knowledge to oppose the vampires, which makes one question the parallels. Was this knowledge leveled for its inaccuracy or for its power to protect? Food for thought…

It’s almost frustrating to witness another predictable, yet realistic, trope manifested through Annie: the Black woman savior. Black women have shouldered and erected many a movement on behalf of the Black community, mostly with the safety of Black men in mind, yet are met with reproach in nearly every aspect of our identities. Black women carry entire communities on their backs only to be downcast as unfavorable by the very community resting within her womb. Through liaisons with white and adjacent women, unbeknownst to the men in participation, these interactions served as a catalyst for the destruction of everything they’d built and a Black woman picked up the pieces. A Black woman who rejected colonial religion. Circling back to the Lord’s Prayer, which Remmick quoted and mocked, exemplifying its lack of power, we see one of many exhibits that renounce the compatibility of this religion with those it was forced upon. As a mortal demon, God’s word should have choked Remmick as one would believe holy water or entrance into a church would. Instead, it had no effect, neither in protecting Sammy nor destroying Remmick. Annie’s Hoodoo, however, proved otherwise on several occasions.

First, we note that Annie had given Smoke, her love interest, an amulet containing a mix of herbs and metaphysical substances. She expresses to Smoke that it’s a ward of protection that ultimately saves him from the vampire in hand to hand combat. As a practitioner of Hoodoo, Annie was the first to recognize that Stack may still be “alive” after Mary’s attack, compelling the group to lock him behind the door, and she knew before the rest that Cornbread was “dead” when he requested re-entry into the juke. She also knew to toss garlic water on Stack after he escaped the room, sending him fleeing from the establishment, as well as tactics she shared for combatting the vampires like driving a stake through their hearts. Without Annie, the climax and resolution of the film would have looked a lot different. This is a testament to the gravity of practicing what works for your specific community. Perhaps Christianity was the perfect vehicle for Europeans, but it neither worked for Remmick, the Irish, nor did it work for any of the Black characters. Hoodoo is comprised of many African parables and customs while the former is derived from teachings that seek to admonish Blackness (i.e. the curse of Ham).

To be clear, I am a Christian as I believe in the death and resurrection of Christ but as I probe into the roots of the culture in which I was raised, I struggle to understand where my belief in Christ fits in with new revelations. I straddle a fence between African spiritual practices and Christian communion, which requires that you eat the body and drink the blood of Jesus, and media that pique my interest in learning more about ancient African customs further augment the figurative fence until it’s too tall for me to gain footing on either side. I feel that Sinners, in all its horrific, cinematic glory, with every motif present, calls upon us to question religion, identity, and allyship in the Black community. How do these aspects of our personhood benefit us, and if not, how do we go about expelling them for the greater good of the culture?

Ryan Coogler, producer of Marvel’s Black Panther series, another amazing collection of Afrocentric movies responsible for the second awakening of the Afrofuturism genre, is an artist capable of engaging storylines, thrilling motion pictures, and inciting conversation surrounding sociocultural norms and history in African American communities. On numerous occasions he has stimulated sentiments of pan-African pride within a community bereft of identity and connection.

Coogler, time and time again, has left me with much to inquire about in relation to the history of Black people in this country. The intention with which he details every scene, the historical accuracy, the metaphors–I’m gluttonous for insight. I know certainly I’m not alone in this endeavor as we should each interrogate the fabric of American society and determine in which ways do we lack compatibility with its standards. For his contribution to the Black literary canon, Coogler is a living legend in my book. If you haven’t already, I implore you to watch Sinners, which is now streaming on HBO Max, and if you’ve already indulged, share with me your thoughts and analyses with understanding. Thank you for reading.

Please like, share, and subscribe if you have been fed to fulfillment by this article. Join the conversation by sharing your observations below. Thank you, dear reader, for your support.

Join the conversation!