Today, September 15, 2025, kicks off Hispanic Heritage Month, so I’m excited to share with you a few pieces of Latin history and literature in celebration of a heritage that’s made such an impact on history as we know it. Between today and October 15th, join me every Monday for retellings of prominent events in Latinx history, and every Thursday for a book review by a Latinx author. It’s important to highlight the impact Latinx culture has had on not only America, but the entire world because it is woven into even the most mundane aspects of our lives. Let’s start this braid with the history of Hispaniola. That being said…

Let’s weave a story, beginning with an island. Let’s call this island Hispaniola.

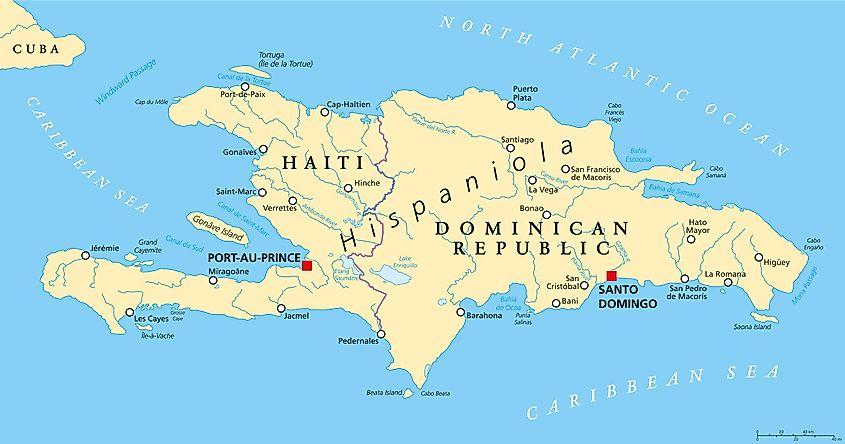

Before it was divided by borders and burdened by history, this island was called Ayiti, or Quisqueya, by its first inhabitants: the Taíno people. For centuries before European contact, they fished its turquoise waters, cultivated cassava and maize, and lived communally, governed by caciques—chiefs whose authority was rooted in reciprocity rather than conquest. But you remember that little rhyme they taught us in school? Christopher Columbus sailed the ocean blue in 1492–yeah, history from this point isn’t as cutesy as the song leads on. Christopher Columbus, on his infamous voyage, stumbled upon this island, which he christened La Isla Española—the Spanish Island. This land was pivotal, a jewel in Spain’s growing empire. From the capital city of Santo Domingo, Spanish explorers would later launch

expeditions that altered the entire Western Hemisphere: Ponce de León sailed north and stumbled upon Florida, Vasco Núñez de Balboa “discovered” the Pacific, Hernán Cortés brought down the Aztec Empire in Mexico, and Francisco Pizarro did the same to the Incas in Peru. Hispaniola became the heart from which Spain’s colonial ambitions radiated.

To the Taíno, however, this new era brought only devastation. The Spanish implemented the encomienda system, forcing the Taíno into grueling agricultural and mining labor under the guise of “Christianizing” them. By 1501, recognizing that the indigenous population was collapsing under this brutality, King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella issued a charter permitting the importation of enslaved Africans. By 1503, the first African captives arrived, ushering in a transatlantic system of forced labor that would shape the island’s future for centuries. Spaniards believed Africans were “better suited” for the backbreaking labor, a racist ideology that fueled the rise of chattel slavery in the Americas. Demographic data exported from 1514 revealed a horrifying reality: a 3.5% annual population decline, driven by starvation, disease, and violence. Entire communities were decimated. When Taíno leaders resisted, they were killed.

By the 1600s, Spain’s grip on Hispaniola weakened. Many Spanish settlers abandoned the colony, leaving vast tracts of land ungoverned. Into this vacuum crept smugglers, cattle ranchers, and French colonists, particularly in the northwestern region. The small island of La Tortue became a notorious base for French buccaneers who harassed Spanish shipping routes. By 1625, French settlers had established a permanent foothold. In 1697, the Treaty of Ryswick ended the Nine Years’ War between France and a European coalition comprised of Spain and Great Britain. As part of the treaty, Spain formally ceded the western third of Hispaniola to France, which renamed it Saint-Domingue. The island was then split into two: Spanish-controlled Santo Domingo (today the Dominican Republic) in the east, and French-controlled Saint-Domingue (today Haiti) in the west. This division would set the stage for centuries of conflict and revolution.

By the late 18th century, Saint-Domingue became the most lucrative colony in the world, exporting sugar, coffee, indigo, cocoa, and cotton. Its wealth, however, rested entirely on brutality. By 1789, over 500,000 enslaved Africans labored under abysmal conditions to enrich 40,000 white planters and 25,000 free people of mixed ancestry (mulattoes). Though mulattoes technically held French citizenship, they faced systemic discrimination and were denied full social and political equality. Resistance simmered beneath the surface. Runaway slaves, known as Maroons, waged guerilla attacks on plantations, seeking freedom and weapons. From 1751 to 1757, legendary Maroon leader François Macandal led a fierce rebellion before he was captured and burned at the stake in 1758. His martyrdom foreshadowed the massive upheaval to come.

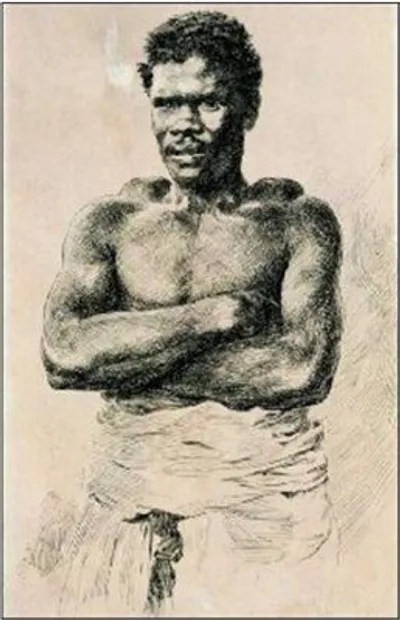

Then came the French Revolution of 1789, echoing across the Atlantic with its rallying cry of Liberty, Equality, Fraternity. On August 22, 1791, enslaved people of Saint-Domingue rose in the largest slave revolt in history, burning plantations, killing slave owners, and toppling the colonial hierarchy. This rebellion launched the Haitian Revolution, a more than decade-long fight for freedom. At first, the rebellion was fragmented. Mulatto leaders like André Rigaud and Alexandre Pétion led separate campaigns, while Black revolutionary forces sought to unify. Emerging from this chaos was Toussaint L’ouverture (1743-1803), an educated formerly enslaved man whose brilliance as a strategist earned him the title “the Black Napoleon.” After France officially abolished slavery in 1794, L’ouverture sided with the republic and fought to establish an independent Black-led state.

However, internal tensions persisted. When mulatto factions resisted L’ouverture’s vision, civil war erupted, culminating in Rigaud’s defeat by 1800. L’ouverture controlled the island, but French ruler Napoleon Bonaparte had other plans. Fearing Haiti’s independence, Napoleon sent 20,000 troops under General Charles Le Clerc—his own brother-in-law—to retake the colony in 1802. Though L’ouverture’s armies were equally strong, betrayal struck. His lieutenants, Jean-Jacques Dessalines and Henri Christophe, defected. On May 5, 1802, L’ouverture surrendered under false promises of peace. Instead, he was captured, shipped to France, imprisoned, and killed on April 7, 1803. Ironically, yellow fever soon ravaged the French troops, killing Le Clerc himself.

Even without L’ouverture, the fight continued. Dessalines assumed leadership and decisively defeated the French. On January 1, 1804, he declared Haiti independent—the first free Black republic in the world. But freedom came at a staggering price. In 1825, French King Charles X agreed to recognize Haiti’s independence only if Haiti paid 150 million francs (approximately $40 billion ca. 2025). To meet this demand, Haiti was forced to take out high-interest loans from foreign banks, plunging the new nation into crippling debt. Even after the amount was reduced to 90 million francs

(~$24 billion ca. 2025) in 1838, Haiti spent 122 years repaying it, finally completing the last installment in 1947. Dessalines himself was assassinated in 1806, sparking a civil war between northern and southern Haiti that lasted until 1820. Leaders like Christophe, Pétion, and others shaped this turbulent period, often excluding Black Haitians from political power despite the revolution’s ideals.

While Haiti battled for survival, the eastern part of the island remained under Spanish control as Santo Domingo. However, in 1821, a rebellion erupted, with Dominicans seeking independence from Spain. Their aspirations were quickly derailed when Haitian President Jean-Pierre Boyer invaded in 1822, forcibly reuniting the island under Haitian rule. This union lasted until 1843, when Boyer’s government was overthrown. Seizing the moment, Dominicans declared independence on February 27, 1844, forming the Dominican Republic. Yet independence was fragile. Many Dominicans feared retaliation from Haiti, a much larger and stronger nation. In 1861, the Dominican Republic voluntarily returned to

Spanish colonial rule to seek protection, only to regain independence again in 1865. Though divided, the island’s history is inextricably linked. Its lands have seen glory and grief, from the Taíno’s first footsteps to the revolutionary fires of L’ouverture and Dessalines, to the modern struggles for sovereignty and identity. Today, Hispaniola stands as a testament to resistance and resilience. When we honor Hispanic Heritage Month, we must also remember the Indigenous Taíno, the enslaved Africans, the revolutionaries, and the everyday people whose lives shaped this complex legacy. Hispaniola is more than an island—it is a mirror reflecting the intertwined histories of oppression, liberation, and the unyielding pursuit of freedom. Thank you for reading.

Please like, comment, and share to expand our conversation. Subscribe to The Plait to receive biweekly post notifications and never miss another strand again!

Sources:

“Dominican Republic.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, inc., 9 Sept. 2025, http://www.britannica.com/place/Dominican-Republic.

“The Franco-Spanish Rivalry for Control of Saint-Domingue.” Gallica, gallica.bnf.fr/dossiers/html/dossiers/FranceAmerique/en/D2/T2-4-1-a.htm#:~:text=The%20present%2Dday%20division%20of,western%20third%20of%20the%20island. Accessed 15 Sept. 2025.

“Haitian Independence: Research Starters: EBSCO Research.” EBSCO, http://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/history/haitian-independence. Accessed 15 Sept. 2025.

“The Hemisphere: Hispaniola: A History of Hate.” Time, Time Inc., 7 May 1965, content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,898728-1,00.html.

“Hispaniola: Research Starters: EBSCO Research.” EBSCO, http://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/geography-and-cartography/hispaniola. Accessed 15 Sept. 2025.

“The Island of Hispaniola Is Founded.” African American Registry, 6 Dec. 2024, aaregistry.org/story/hispaniola-founded/.

“Timeline: Haiti’s History and Current Crisis, Explained.” Homepage, concernusa.org/news/haiti-timeline-history/#:~:text=1697:%20Saint%2DDomingue,and%20is%20assassinated%20in%201806. Accessed 15 Sept. 2025.

Join the conversation!