Join me, reader, in weaving a story, and like always, we’ll begin with a poet. Let’s call this poet Elizabeth Acevedo.

Elizabeth Acevedo is an award-winning author of an array of books centering on the Afro-Latinx experience. She was born in New York City to Dominican Parents, and has obtained a Bachelor of Arts in Performing Arts from The George Washington University and a Master of Fine Arts from The University of Maryland. A National Poetry Slam champion, Acevedo is known for delivering awe-inspiring, thought-provoking, tear-inducing poetry performances that incline listeners to think twice about identity and belonging, especially for young Black women.

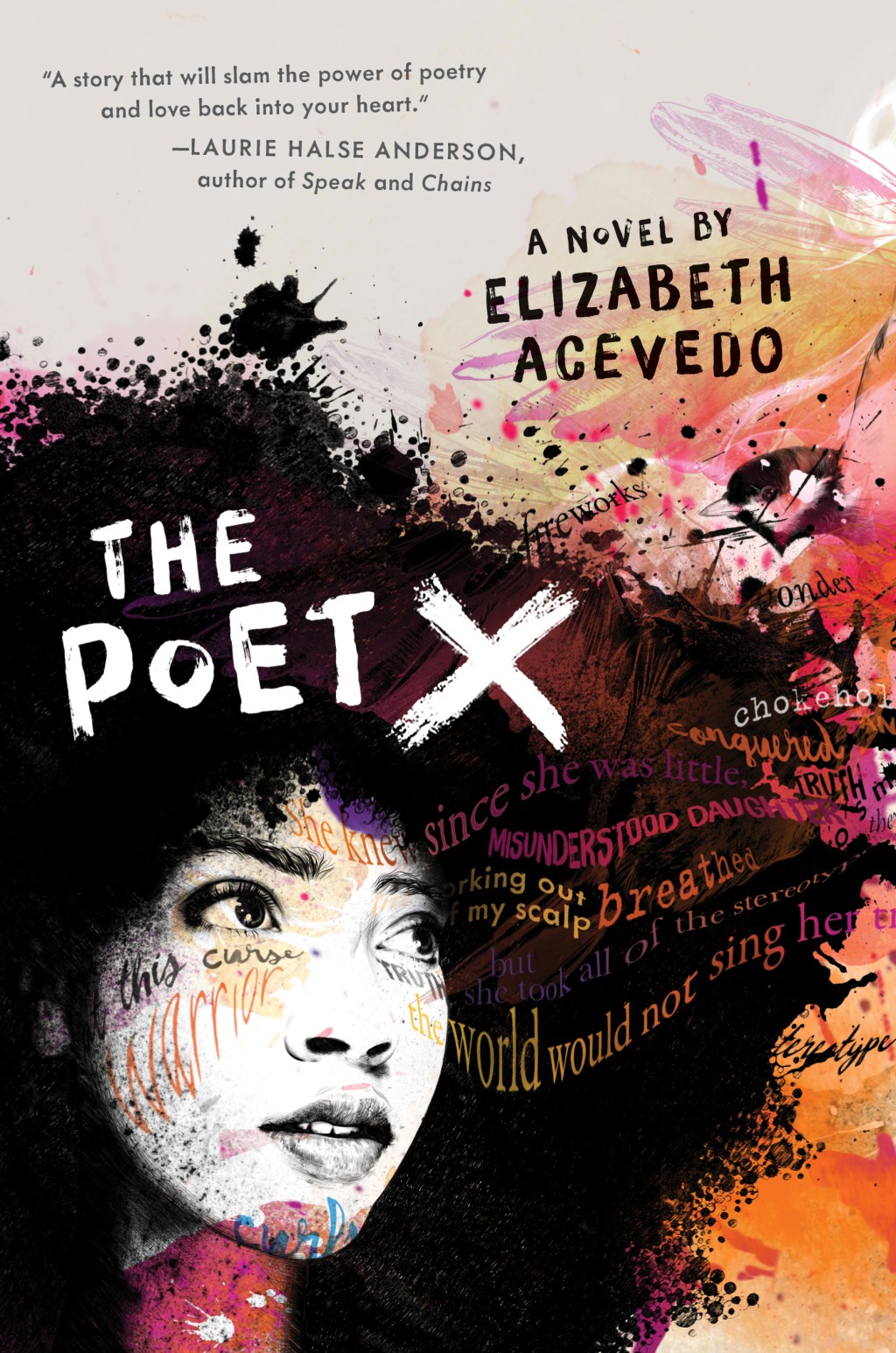

For her work she was awarded the 2022 Young People’s Poet Laureate, an honor reserved for those who have devoted their careers to writing exceptional poetry for young readers. She wrote With the Fire on High (2019), which earned best book of the year by the New York Public Library, NPR, Publishers Weekly, and School Library Journal; and Clap When You Land (2020), which was a Boston Globe-Horn Book. My favorite of her works–and arguably the most acclaimed–is The New York Times bestseller The Poet X (2018), a story in verse detailing the coming-of-age of a fifteen-year-old girl named Xiomara. This masterpiece won the National Book Award for Young People’s Literature, the Michael L. Printz Award, the Pura Belpré Award, the Carnegie medal, the Boston Globe-Horn Book Award, and the Walter Award.

“I am unhide-able. Taller than even my father, with what Mami has always said was ‘a little too much body for such a young girl’.”

Elizabeth Acevedo, The Poet X (2018)

If someone had handed me Elizabeth Acevedo’s The Poet X when I was fifteen, I think I would’ve cried from relief. Not just because it’s beautifully written, which it is, but because it made space for the things I had no language for back then. Xiomara Batista is a fifteen-year-old Afro-Latina growing up in Harlem with a body that draws attention she never asked for, a voice no one wants her to use, and a family–especially a mother–that tries to force her into silence in the name of God. This novel-in-verse does what so few books dare to do: it gives voice to the inner lives of girls like us. Full-bodied girls. Dark-skinned girls. Girls raised in the church who are taught to fear our own bodies, our own thoughts, and even our own questions. Reading The Poet X felt like reading the parts of myself I had always been taught to repress.

From the very first pages, Acevedo captures what it feels like to live in a body that doesn’t get to be your own. In the poem “Stoop-Sitting,” Xiomara writes: “I am unhide-able. Taller than even my father, with what Mami has always said was ‘a little too much body for such a young girl,” and “After it happens when I’m at bodegas. It happens when I’m at school. It happens when I’m on the train. It happens when I’m standing on the platform. It happens when I’m sitting on the stoop. It happens when I’m turning the corner. It happens when I forget to be on guard. It happens all the time. I should be used to it. I shouldn’t get so angry when boys—and sometimes grown-ass men—talk to me however they want, think they can grab themselves or rub against me or make all kinds of offers. But I’m never used to it. And it always makes my hands shake. Always makes my throat tight.” I remember what it felt like to be 13, 14, 15 and already treated like a grown woman. The stares from men, the side comments from adults, the judgmental looks from aunties who thought I was “fast” just because of how I looked. Like Xiomara, I didn’t ask to have curves. I didn’t ask for attention. But somehow, the world treated my body like a crime scene. There was never any grace, never any conversation, just rules. What to wear, what not to wear, how to sit, how to speak, when to be invisible. And when Xiomara talks about how she started shrinking herself just to stay safe, I felt that. Because I learned to do that too.

Acevedo doesn’t just talk about the body; she talks about how Black and brown girls are silenced in their own homes. One of the most emotionally raw and familiar aspects of The Poet X is the strained relationship between Xiomara and her mother. Raised in a deeply religious household, Xiomara is expected to follow Catholic doctrine blindly, to go to confirmation classes, avoid boys, and repress her curiosity about sex, love, and God. I grew up in church, too (both African and Black American churches) and while there was love there, there was also control. There were rules about what you could wear, who you could talk to, and most of all, what you could ask. There was no room for doubt, no space to question, and certainly no safe way to say, “I don’t feel God right now.” Like Xiomara, I eventually started to reject God. Not because I didn’t believe, but because the version of God I was being handed didn’t feel like love. It felt like fear. Like punishment. Like a constant reminder that I was falling short. When Xiomara hides her poetry journal the same way someone might hide contraband, it reminded me of how I used to write poems, songs, and short stories to myself in secret just to process my emotions. There was no space to say, “I feel like I’m drowning,” because I was expected to be strong, to be silent, to be perfect. Xiomara’s poetry becomes her salvation; her way of reclaiming agency in a world that denies it to girls like her.

Then there’s the matter of love. First love, forbidden love, the kind that simmers beneath the surface because you’re not “allowed” to want it. Xiomara’s crush on Aman, her classmate, unfolds slowly and delicately, and it’s beautiful because it’s so real. She’s not rushing into anything; she just wants to be held, to be seen, to be understood without being objectified. The absence of tenderness in her own household makes her need for emotional intimacy even more intense. I remember that feeling, liking someone and not knowing what to do with it because I wasn’t even allowed to talk to boys. Having crushes was like having secrets, and every part of it felt wrong, even when it was just innocent. The tension Xiomara feels with her twin brother, Xavier (whom she calls Twin), is another layer Acevedo gets right. Their bond is quiet but deep. Xiomara fights for him when he can’t fight for himself, defending him when he’s bullied. And yet, she feels hurt when she finds out he’s been carrying a secret without her: his queerness. I know what it feels like to fight for your siblings, to protect them, to carry them when you’re barely standing, but to still feel misunderstood by them, too. That quiet grief of not being fully seen even by the people closest to you is real.

“And I think about all the things we could be if we were never told our bodies were not built for them.”

Elizabeth Acevedo, The Poet X (2018)

What makes The Poet X work so well is that it doesn’t try to solve everything. It doesn’t offer some perfect, polished version of healing. Instead, it gives us a girl who is still in process. Xiomara isn’t perfect. She pushes back, she lies, she hides, but she also grows. She finds her voice through slam poetry, and when she performs her work in front of an audience for the first time, it’s not just cathartic. It’s revolutionary. She takes back the space that was denied to her. She writes, “And I think about all the things we could be if we were never told our bodies were not built for them.” That’s the core of it; the ways the world limits us before we even get the chance to try. Acevedo didn’t write a neat story about a girl growing up. Instead, she wrote a raw, tender, furious one. One that tells the truth about being a girl of color in a world that tries to quiet us before we’ve learned to speak. Her verse is lyrical, but never fluffy; emotional, but never manipulative. It felt like every poem cracked something open in me, like someone was finally telling me, “You’re not wrong for feeling this way.” For high school readers (especially girls, especially those from immigrant families, especially those who grew up religious) The Poet X is essential. It doesn’t just belong on our shelves; it belongs in our hearts, in our journals, in our classrooms. It’s the kind of book you want to annotate, reread, and give to your best friend with dog-eared pages and underlined lines that made you cry. It’s a reminder that our voices matter, even when they shake, even when they go unheard, even when the world tells us to hush.

Like Xiomara, I felt the weight of gender roles heavy on my back. I had to be obedient, responsible, nurturing, but not outspoken, not independent in a way that threatened tradition. I wanted freedom, but I also wanted to be good, and those two things felt mutually exclusive. Religion only made that harder. Faith was supposed to be comforting, but most of the time, it felt like a rulebook I was failing to follow. Like Xiomara, I found safety in close family friends, the ones who just let me exist without expectation. And like her, I found comfort in words: in books, in writing, in anything that made me feel like I wasn’t crazy for feeling this way. Looking back, I realize how much of my teenage years were spent fighting battles I didn’t even have words for yet, battles The Poet X captures perfectly. Xiomara’s story isn’t just hers; it’s the story of every girl who’s ever been told she is too much and not enough at the same time. It’s more than just a book. It’s proof that young girls of color deserve to see themselves in stories where they are complex, flawed, brave, and beautiful. And most importantly, it reminds us that we are allowed to speak. Loudly. Unapologetically. In our own words. Thank you for reading.

Please like, comment, and share to expand our conversation; and subscribe to The Plait for biweekly newsletters delivered directly to your inbox. Clink the link below to visit Elizabeth Acevedo’s website and dive deeper into her world of poetry.

Join the conversation!